Articles Vancouver Courier

Bird brainiacs: Where tech meets bird-watching

Bird-watching is social, hip, 'geeky in an intellectual way,' and surging thanks to technology

by Megan Stewart

Posted on May 23, 2017 at 3:07 PM

Showing the Facebook live feed of the bushtits nesting on her Mount Pleasant balcony, artist Jennifer Chernecki says bird-watching is social and 'geeky in a grown-up intellectual kind of way.' - Photo Dan Toulgoet

For the second spring, Jennifer Chernecki welcomed two bushtits back to her Mount Pleasant balcony.

“I call them my tenants but they are completely wild,” she said. The brown songbirds delighted the artist who could spend hours observing their enchanted, twitchy habits as they went about building a new nest for the season.

She paints them, has named them Fudgie and Titty, and stages her patio as a kind of urban nature documentary since she started filming the bushtits live on Facebook.

“I just can’t resist,” she said. “Sometimes I want to call it the ‘Titty cam.’”

Chernecki, 33, is a bird-watcher who only just saw herself as such. “Birder is not a term I had ever used until this moment, but I do study birds, paint birds and visit places specifically to see birds. I used to raise birds when I was a child,” she said earlier this month before Bird Week, the city’s annual effort to create awareness about the region’s ecological health and winged-thing biodiversity.

Birding is surging. As one of those millennials who effortlessly forges technology into her art practice and relationship with the natural environment, Chernecki is an example of today’s modern birder.

“It’s social and kind of geeky,” she said. “That is a very hipster thing to do. Geeky, I say that with tongue in cheek because I mean geeky in a grown-up intellectual kind of way.”

Geek chicadeedee

As one of the fastest growing hobbies on the continent, according to Bird Studies Canada, bird watching is lifted by municipal events such as this city’s Bird Week. In 2018, Vancouver hosts the International Ornithological Congress and selected an official city bird, the Anna’s hummingbird, in a city-wide vote.

Bird watching was labelled the “unlikeliest craze” of 2017 by vacation tome, Conde Nast Traveller. Vancouver’s Bird Week appealed to young adults and early-30-somethings in an event called the “rise of the hipster bird-watcher” and lured them with a free download of EyeLoveBirds, a sophisticated and attractive birding app created by Vancouver developer Erynn Tomlinson, a Mount Pleasant birder who doesn’t live far from Chernecki. The name of the event was inspired by the Telegraph newspaper, which described the naturalist pastime “the new must-have string to the millennial’s bow.”

Also newly popular with young British men, according to a national survey in the U.K., in Canada, an average one in five people are active birders who spend more than a quarter of the year watching birds. More than half are women. According to the Canadian Nature Survey, bird watching is even more popular than gardening.

Birds are an indicator of a healthy ecosystem, and in an urban landscape made from concrete and glass, birds are still one way people regularly (and mostly positively) engage with wildlife. It has cache as a bonafide scientific study that contributes to local and global habitat conservation efforts, another goal supported by technology and data collection.

Band of birds

Bird banding – the practice of affixing a light-weight tag with a unique identifying number to a bird – is one way biologists the world over track bird movement and migration.

“If you put a band on a robin here, and it flies down the US or south for the winter, you can actually see if another biologist or birder catches this same bird and report it on the system,” said Hannah Nieman, 28, a bird-watcher who works with a water conservation non-profit organization and is interested in habitat restoration.

“You can see where that bird goes. You can see that these birds have patterns. We have a lot of species at risk, especially with climate change, it’s really important to see how they are doing one year to the next and in large patterns,” she said.

As someone who has been birding since she was a child, Nieman now uses software to learn bird calls and better identify species just from their song.

“It’s helpful to fine-tune your ear,” she said.

With apps like Warblr and others, bird watching can quickly become bird listening, like being in the audience as an orchestra performs and trying to isolate the first violinist.

“It’s not just about using your visual senses but also your auditory senses. It’s almost like you can hear all these different songs and then focus on one. You can hear its particular tune through everything else,” she said. “It makes me feel really at peace.”

That something for all generations.

Read on VanCourier.comLove on the run: Couple to wed during Vancouver marathon

Talk about relationship goals.

by Megan Stewart

Posted on May 5, 2017 at 6:17 PM

'We are romantics,' says James Makokis (left) about himself and his fiancé, Anthony Johnson. The couple will take a pause from their long-distance road race to get married at the 32-kilometre mark of the Vancouver marathon on May 7, 2017. - Photo Dan Toulgoet

Two runners will start the BMO Vancouver Marathon on Sunday as an engaged couple but by the time they cross the finish line 42 kilometres later, they will be married.

Along the way, Anthony Johnson and James Makokis will stand tall as gay, aboriginal role models in a public display of commitment and love. And imagine, most runners are satisfied with a personal best time.

Johnson and Makokis, 31 and 35, will say their vows under a hand-hewn poplar arch near the lofty diamond ring sculpture in English Bay, wearing matching tuxedo jackets over shorts and sneakers in the company of their closest relatives and thousands of marathoners.

“Yes, we are romantics,” said Makokis, who is Cree. “We are also role-modelling for people of our nations and other communities.”

For the wedding, both of their mothers will lay down a carpet of cedar in an expression of unification while, like flower girls, they also drop petals along the pathway. Johnson’s sister will sing traditional songs in several indigenous languages and play a rattle. Makokis’s father will smudge the grooms.

Once married by a justice of the peace, the men will run the remaining 10-km circuit around Stanley Park with a gilded partnership and weddings bands.

Spectators wishing to celebrate the couple are encouraged to bring flowers and other organics.

“This is the city we fell in love in last year,” said Johnson of Vancouver. He moved north from the U.S. to live with his fiancé outside Edmonton where they run a technologically advanced, conservation-minded, agrarian-based homestead. “We’ve always been adventurous in our relationship."

When they moved into their current home, they found a small inukshuk in the yard and now, by coincidence, their wedding will take place near the 20-foot inukshuk on the shore of English Bay. "It's another token of the universal love that has been given to us," said Johnson.

As two-spirit aboriginal men, the couple is pleased to declare their love out in the open for all the city to witness while also promoting exercise as time well spent together. Talk about relationship goals.

“Doing this in Vancouver was an opportunity for us to be visible, as gay men, as two-sprit men and as indigenous peoples, as young people. It’s important for us to have visibility,” said Johnson, who is Navajo and spent his teen years in Phoenix before graduating from Harvard and then moving to Brooklyn.

“We have the opportunity to say to young queer out there, they can have whatever they want in their lives as well. To show indigenous people that you can exercise, you can run, you can move your body, you can be well, and you can take part in something and have friendship and relationships along the way.”

Johnson said he had never run more than eight miles, while Makokis has completed the Vancouver marathon half a dozen times since 2002. Even their first road race together was eventful; they ran in the New Year on a 10km race course in Phoenix. In case you didn't catch that, it was a midnight run.

Running brought them closer to each other and the immense beauty of the places they call home, especially since, as dedicated professionals, they often trained at night, in the dark outside through a prairie winter in -30 degree temperatures accompanied by snowdrifts and starlight.

“The land is completely still, everything is quiet, the snow has this blue glow and then sometimes the Northern Lights would be out,” said Johnson. “Running at night is really magical.”

They wondered why more runners do not head out after dark. It's one more example they're setting.

Exercising together also solidified their connection, said Makokis, a family physician who serves two Cree communities and also runs a practice dedicated to transgender patients.

“I feel running is a really good metaphor for life, for relationships. It takes work for it to work. If you don’t put in the effort, then it won’t turn out well in a lot of the cases, so I really value the time that we get to spend together when we are training because we are doing something positive so we will live long, healthy lives together."

The BMO Vancouver Marathon is Sunday, May 7.

Read on VanCourier.comVancouver grandmother on risks and metaphysics before Marathon Des Sables

Sand, snakes, sun just three of the obstacles in Sahara Desert six-stage ultra-marathon

by Megan Stewart

Posted on April 4, 2017 at 4:47 PM

At 59 years of age, Pushpa Chandra could be the oldest Canadian woman to complete the famously difficult Marathon Des Sables, which begins in the Sahara Desert in the south of Morocco April 9, 2017. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Running for six days through sand, sun and wind on a still-secret trail through the Sahara Desert won’t be the hardest thing Pushpa Chandra has done in her life. It will be one of many hard things, and the ultra-marathon runner embraces the matter as fact. The race is difficult and that’s the point.

“I would not really call anything hard. As an adventure runner, the challenges are always what you are looking for,” she said in March, a week before flying to Europe to then travel on to Morocco for the famed Marathon Des Sables, a 250-plus-kilometre, self-supporting stage race with six days of running a route that has changed every year since the inaugural event in 1986 when 23 runners took off together.

The sparsely marked trail over dunes and rocky, technical hills called djebels will be revealed only moments before the race begins on April 9. The first stage this year is 33.8 km. The longest leg comes on day four, at 81.5 km.

“I will run, I will walk, I will crawl if have to,” she said. Chandra will finish.

Racing the world

It’s a mental and physical battering that comes with the risk of serious injury and tests a runner’s deepest reserves. Besides, this race can kill.

Participants in the Marathon Des Sables are advised to have their vaccinations updated because, according to race organizers, polio is “still rampant in the area.” Runners are encouraged to carry anti-venom kits and are given specific quantities of water each day, depending on the length of the stage, from 30 to 81 kilometres.

When a sandstorm hits, runners must stay where they are and wait for instructions to avoid drifting off track where they could be swallowed by the desert. The worst storms can last eight hours. In the short history of the Marathon Des Sables, the “marathon of the sands” in French, three people have perished. The Discovery Channel labelled this ultra-marathon the toughest foot race on Earth. To prepare for the Marathon Des Sables, Chandra maxed out her training at 312 km a week, running inside on a treadmill to help acclimatize to exercising in the heat. “You want to run as much as your body can tolerate,” she said. “At this distance, we go by how many hours we run. Most of us know our pace by now, training anywhere from four to 12 hours a day.”

And there is something more. Chandra is 59 years old.

“For this race, I was feeling, like, Oh my gosh, I am so old,” she said, wondering if the ultra-marathon was even possible for her. Yes, she determined it was.

“Running is not just another form of exercise. It offers so much more than exercise,” she said. “It has transformed me to another level. I call it moving meditation. It offers me countless hours of solitude and silence and all I hear is the steady pounding of my feet. There are all these thoughts about life and the big picture of our lives.”

The grandmother is often among the oldest participants and one of the few women to run multi-stage races on every continent, including the Antarctica 100 as the first Canadian to take it on. She set a record that stood for four years. Running at the other end of the Earth, she took the women’s title in the North Pole Marathon in 2009. She’s taken on the Mount Everest Marathon, the Amsterdam 100, and run 250-km self-supported races in Madagascar and the Gobi Desert.

Chandra signs up to wander into the unknown, on the trail and in herself.

“The ultimate journey is about not knowing what the risks will be and that is what really empowers you. I want to go through the journey of not knowing… I know I can do it but I don’t know what changes I am going to go through. There is this risk of unknown that you want to explore,” she said.

Follow Chandra live online as she works towards completing the Marathon Des Sables. She is runner no. 709.

A backpack to rule them all

In seven kilograms on her back, Chandra will carry almost everything she needs to sustain and shelter herself over six days and 250 kilometres in the Sahara Desert. In this race, preparation is absolutely everything.

Weighing slightly more than a large can of paint, her backpack will be carefully loaded with high-protein macadamia nuts and freeze-dried vegetarian lasagne, each serving tightly packed, the caloric counts on display, and labelled for days one through six. She will heat water under the desert sun to cook her food and will truck around mandatory equipment like a headlamp and extra batteries, 10 safety pins, and at least 200 euros. Required safety equipment includes a compass, whistle, signalling mirror and tropical disinfectant. She’ll also have an anti-venom pump to treat any poisonous bite from a desert horned viper.

She will carry a photograph of her mom.

She won’t double-up on any equipment but said she “just invested in the lightest and strongest gear and tested it over a few months in advance.”

Water bottles will attach to the shoulder straps, the stras within reach of her mouth for hadns-free and consistent hydration.

She’ll carry a slim sleeping bag when the over-night temperature drops to 14C degrees, tights and merino wool for nighttime as well as a balaclava, which “is also for sand storms,” she said. She will have the most simple toiletries of a toothbrush head and soap tablets. There will be no showers until the seventh day and she will tend to her feet with “lots of blister prevention and treatment supplies, including tapes and needles for popping blisters daily.” Taking care of her foot health is one of the most inportant daily tasks (a chore, really) she will face. Blisters are the top injury among all runners.

At night, Chandra will sleep on the ground in an eight-person Berber tent made from goat’s hair. She will bunk with seven women from the UK whom she met on a training trip in the Canary Islands, a new group of friends that make better bunk-mates than men, whose loud snores and especially smelly feet have previously disrupted her sleep. She will take a natural sleep aid because rest will be essential but fleeting.

Each day she will get a prescribed amount of water to drink and use for cooking. Runners suffer time penalties if they toss any trash in the Sahara, fail a random equipment check, or carry a bag weighing more than 15kg.

Crocodiles of the mind

During the 150-km, six-stage Racing Madagascar event three years ago, Chandra became severely dehydrated and was at risk of heat stroke. As a retired registered nurse and practising naturopathic doctor, she recognized the dangerous warning signs of nausea, dizziness and hyper-ventilation. “You can’t put one foot forward,” she said.

Accepting medical intervention from the on-site first-responders would mean immediate withdrawal from the race. Similarly, if they determined she was not fit to continue, her race would be over. Still on the very first stage and resolute to continue, Chandra treated her symptoms on her own.

To slow her breathing despite the 45C temperature, she folded herself over a small tree and poured water over her head. The afternoon heat was reaching its peak, so she counted herself lucky she neared the end of the 20-km stage and could walk to the finish line in 30 minutes. In what would have been an uncharacteristic first, she was ready to pull out of the race that night.

“The next morning, I woke up and I didn’t think I could survive this next passage because the terrain was so gruelling,” she said of the 26-km facing her that day. “Something came up in my mind. Remember, you don’t have a choice to pull out… You have to wait for someone else to tell you to pull out. That is one of the mantras I practise. This is part of that discipline that comes with going through those landscapes. It is a power that answers, You can do this. Someone else has to tell you can’t do this.”

It gave her no choice but to go on. If no one else was going to stop her for safety reasons, she sure as sunlight was not stopping herself.

The second stage was even harder. But in Madagascar, she got on with it, telling herself, “I am not over with this. I can go. And that is what I did,” she said. “That is when we crossed a lake with crocodiles in it.”

For the girls

Chandra has been running since she was a child. At the age of five or six, she said she pocketed her bus money and ran the eight miles to school so she could spend the coins on popsicles. “Running always came with a reward,” Chandra said she learned. She ran back home, too, all of that distance covered barefoot. “It took me an hour. Not bad for a little girl,” she said.

Raised by subsistence farmers in Fiji, Chandra grew up in poverty but did not suffer the same sexist expectations that marred the life of her older sister, who was denied an education because she was required to fulfill domestic chores while her siblings went to class.

“Poverty is a cycle that is very hard to break,” said Chandra, who moved to Vancouver more than 40 years ago and lives in Point Grey. “There are 62 million girls in the world that do not go to school. That could have been one of me. Education is really a gift for us in Fiji. Only the privileged get this gift, it is not like in Canada or the developed countries where education is for everyone.

“My sister had to stay home to help my mom get things done so we could go to school, so I could go to school. She made wrong choices in her life, and this is the power of education. It is an intangible that will empower women to make the right choices.”

Chandra is running in support of Plan International, a charity that uses education as the main tool to break the cycle of poverty through campaigns such as I Am A Girl. Her fundraising goal is $1,000.

Run like water

With the motivation to move society forward and closer to deep and lasting equality, Chandra runs and runs as if to spin the axis of the planet and reach the future she believes is coming. One that sees girls and women lifted out of poverty and servitude through the opportunities, agency and self-determination that come with education. A retired nurse who worked in critical care at B.C. Children’s Hospital and now practises naturopathic medicine, Chandra knows the difference education makes in a girl’s life.

When she keeps to a path or takes step after step on a treadmill, Chandra lets her mind wander free. The “moving meditation” she describes is an effortless surrender. “There is no trying,” she said. “It is spontaneous.”

She says it’s like water flowing from a tap. Once you start, you don’t need to do a thing more. “The water starts running,” she said. “You put that one foot forward.”

Don’t mistake her, however. Running hundreds of kilometres is not easy. Remember, the point is that it’s difficult. It’s in the struggle of these moments where Chandra says she finds herself.

“There will be times when you will be going through pain and you learn about this extraordinary discipline,” she said, explaining the “mental games” that keep the tap open and the water running.

“Why are you self-willingly wanting to suffer? When I get to the place of pain and doubting myself, it is really hard when you are there. I look at anything I can see — that tree, or the next rock — and I say, Move one leg in front of the other. Get to that rock. Reach the tree. That is how present you get. I’ve got this rock now, now I’m going to the next one.”

She recites mantras and imagines the pleasure of stopping once she’s reached the finish line and does not have to keep pushing, slogging, hurting. “As soon as you are finished, it’s done. All of the will power, the entire journey, it becomes a springboard for enlightenment. Honestly, you come back a different person. I always feel I am so Zenned out.”

She says the small things don’t bother her. Her patience endures. The weather does not drag her down. “I come back with such a different picture about life, the big picture of life,” she said.

This gives her energy, and she finds her way to seeing the whole forest by looking at a single tree, the next one on the path towards her destination.

Read on VanCourier.comNeedle sweeps part of morning routine at Strathcona playground

'We find something every day,' says daycare coordinator

by Megan Stewart

Posted on March 13, 2017 at 7:01 PM

Veronica Light carries a sharps box as she checks a playground outside the Strathcona Community Centre for trash, such as used needles, that could pose a hazard to children. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Before children arrive at the Strathcona Community Centre for childcare and until school starts in classrooms next door, an adult searches the playground for used needles.

Childcare workers carry sharps disposal boxes as they sweep the grounds multiple times through the day because, as happened earlier this month, a broken crack pipe can turn up near the slides just before class lets out at the end of the school day.

“We find something every day,” said Veronica Light, the co-ordinator of the Strathcona childcare centre. Between Vancouver School Board contractors and staff, including the principal himself, community centre employees and childcare workers, multiple people check the grounds numerous times a day for used needles and other garbage that may contain blood or bodily fluids and present a risk if not properly thrown out.

“I don’t blame anyone who is using I.V. drugs and I feel they are doing what they have to do for themselves,” said Light.

Forty kids attend preschool at Strathcona and another 170 are registered for licensed care provided by the community centre in a city-owned portable and inside the 126-year-old brick schoolhouse in the mornings and afternoons outside of class time.

Roughly 5,000 injection drug users live in the Downtown Eastside, according to a 2013 city profile of the neighbourhood. Some drug users have the wherewithal to poke used syringes into the wood banisters of staircases, which Light believes is a deliberate effort to make them easier to spot and dispose of but also to keep the sharp end concealed from curious little hands.

“I recognize they could be former Strathcona kid or a parent, possibly a sibling, or auntie or uncle," she said. “They are not the enemy. Many people clean up and more people use around here than the garbage we find. There are just some people who, in that state, are not able to clean up their garbage. However, I don’t like finding underwear in the garden.”

The twice or thrice daily sweeps come with anecdotes that might appal residents elsewhere in the city, but the specific reality of living and working and raising children in the Downtown Eastside is one of the reasons the Strathcona Community Centre Association may be offered a unique deal with the park board. The association had been asking for guaranteed annual funding of $200,000, but there is a possibility it will be offered a different operating agreement than the city’s other 20 community centres. The park board will discuss the needs of the centre at its next meeting March 27. In the meantime, the sweeps continue.

It’s a rare morning that Light or Edwin Rodriguez, a daycare staffer who does daily sweeps before children arrive at the centre, don’t pick up and dispose of a used syringe or condom, discarded clothing or human feces. The garbage increases as the weather warms up. Year-round, they find cardboard out in the open beside the school’s brick walls, under stairs, and sheltered below the slides and suspended bridges of the child-sized jungle gym.

When doing a sweep of the small lot, they use a long pincer and small pair of tongs to place hazardous waste such as bloodied gauze, needles, plastic caps and wrappers into secure disposal boxes. On a warm summer day, Light said they can collect as many as 25 needles in their sweep of the school yard and neighbourhood destinations such as MacLean Park. The trash is considered dangerous because it could contain human blood and some items are sharp enough to break skin, making disease transmission a frightening risk.

“It’s Strathcona, so our kids know. They know what all the needle trash is,” said Light, noting the wrapper from a stick of string cheese resembles the clear plastic envelope that houses a syringe.

“Our kids know when we go outside to play, they sit or stand on the side as we do a sweep for anything – for condoms, for any needle trash, any drug paraphernalia, for clothes because sometimes we have clothes here that get discarded, for dog poop and human waste as well.”

In January, the park board was widely criticised after a child reportedly handled a used syringe in a public washroom at the Creekside Community Centre. The gymnasium was doubling as an emergency warming shelter during a cold snap and, after the holiday break, the multiple uses meant patrons with overlapping needs were sharing the public space. The park board has since said it would place sharps boxes in all community centres.

“If I called [park board chairman] Mike Wiebe every time we found a needle, he’d have a full-time job just responding to that,” said Light.

Many children living in Strathcona know to identify the signs and alert an adult, she said. “No one has ever gotten hurt here. I think our kids are pretty savvy about it.”

The Strathcona Community Centre Association made its pitch for additional funding to park board commissioners and more affluent community centres across the city because it is located in and serves an economically depressed neighbourhood. Many high-needs residents disproportionally rely on government subsidies compared to other parts of Vancouver, though Strathcona is not the only community centre dealing with poverty and hungry children.

Nearly one-third of Strathcona families are considered low-income (compared to 16 per cent of families city-wide) and nearly half of those families are single-parent households (compared with 30 per cent across the whole city). The median annual income is about $14,000 in the DTES, though in Strathcona, a section within the larger neighbourhood, Light described a top-fifth of residents who are educated professionals and relative high-earners, some of whom are building additional equity through having purchased a detached heritage house. Those families also send their children to the Strathcona daycare and elementary school and, according to Light, many pay more than the monthly childcare fee to help subsidize poorer households. It’s a donation because the fees are already relatively low, but it’s also one of the ways the neighbourhood cares for its own.

“The families that we have in the neighbourhood who have enough money, somewhat frequently but not all, they recognize they are getting a good deal and they will make a donation,” said Light.

Those parents pay less at Strathcona than they would at almost every other licensed daycare in the city, she said, because the fees are below average and are subsidized to keep barriers as low as possible.

Fees at Strathcona are $175 a month for after-school care, the same as the government subsidy, which Light says is the lowest in Vancouver at a licensed facility.

“That one-fifth recognized that if they were in any other community, they’d likely be paying as much as $532 and so they will make a donation to the community centre association. That is part of the fundraising effort.”

According to the volunteer association that runs the Strathcona Community Centre, about one-third of families enrolled in childcare are eligible for a provincial subsidy because they are considered low-income and receive social assistance. Another third are deemed working poor and are not eligible for a provincial subsidy but still cannot afford to pay the monthly $175. The remaining one -hird of families pay the full fee.

Parents who can afford other options still pick Strathcona for their children, said Light, who lives in the neighbourhood with a family that includes two daughters aged 10 and 12.

“Those families choose to keep them here because it’s safe, it’s high quality childcare. Part of the reason it’s high quality is because of the fundraising and because my staff are kids who grew up in the neighbourhood or who have some sort of connection to the community here,” she said. “I think most of the staff have some sort of realization like, ‘Hey this kid is just like me or like my family situation growing up.’”

Because of its complex demographics that include a concentrated demand for government assistance, the neighbourhood has a high rate of food insecurity, which essentially means people go hungry.

The community centre fundraises to support numerous breakfast and weekend backpack food programs and relies on private donors to fill additional gaps. For example, the preschoolers have a serving of dairy each morning because one donor, whom they call the “cheese and milk man,” gives a dollar for each one of the 40 youngest kids every weekday of the month.

“There are kids who don’t have milk to drink at home,” said Light.

The Strathcona Community Centre Association, along with 13 other associations, is in favour of a wealth distribution model that would see more affluent centres fund poorer ones in other neighbourhoods.

Not all associations support this. Representatives from West Side associations, for example, have argued the community they serve is specific to only those living near its centres.

“It’s not fair for these kids to go hungry,” said Light. “So, yes, it is not our job, and I recognize that a society should not rely on the park board giving money and assistance to feed children because, if all things were working great, there would be no need and no starving children. But I am telling you right now, there are some very serious situations here. When kids are hungry, somebody has to do something.”

Light and her staff face a range of daily challenges that remind them they are working in one of Canada’s most complex neighbourhoods.

The quiet grounds around the school and childcare centre draw people who find shelter under bushes and dry surfaces under eaves. Some areas are well lit, which can attract a person with a specific need. Other areas are in shadow, which affords sleeping. And, when the grass and bushes are full, they provide a sense of privacy for specific kinds of adult business. Almost all the trash gets left behind and, in the morning, kids arrive.

When she opens the door to the back steps of the building to begin her morning sweep, Light almost always finds the same man right outside, sleeping. About a half dozen men return to the respective places they have staked out on the property, she added.

“We’re friendly, but it’s not like we make them coffee,” she said. “There is a certain awareness that this is where childcare happens.”

Light doesn’t know the man who sleeps on the back steps by name, but they have a respectable rapport and she says he leaves once she wakes him.

“These may be people, who as kids, attended here. They are definitely neighbourhood people and, for whatever reason or whatever their issues, they are using outside.”

It’s but one more example of the unique reality of working and living and raising children in Strathcona.

Read on VanCourier.comLittle League: Loverboy sings the anthem, ‘Iron Pony’ next at bat

by Megan Stewart

Posted on July 24, 2015 at 2:37 PM

If you head to the Joan and Phil Lake Diamond on West 41st Avenue at Vancouver's Memorial Park South this week, you’ll have the chance to cheer for kids named “Sharpie,” “Gunslinger,” “Iron Pony” and “The Not-so-hefty Lefty.”

The nicknames of many Little League players are listed on team rosters and you can decide if White Rocks’ “Big D” Darius Opdam Bak lives up to his sizeable name.

The majors Little League B.C. Championship continues this week at the ball park named for South Vancouver Little League’s past president, Joan Lake, and her late husband, the committed groundskeeper, Phil Lake. From top to bottom, with the exception of one administerial staffer at the national office, Little League operates entirely on volunteer power. Managers, coaches, vice-presidents, score keepers, raffle sellers and that guy who waters the infield give their time and energy to make the league run, as is the case across amateur sport. The umpires are paid. When the outfield fence blew over in a gust of wind earlier this week, spectators co-operated to put it upright.

The diamond last saw provincial action in 1985, when Trail won the title over a team from Coquitlam. A player from that 30-year-old championship team has returned to Memorial South this week to watch his son compete, also for Trail.

For a mid-week game, Mike Reno sang the national anthem. The Loverboy rocker encouraged the 11- and 12-year-old players with this rousing message, "Turn 'em loose, boys!"

On Wednesday afternoon in what was widely anticipated to be the teams that meet in the championship final, White Rock shut out Little Mountain 8-0.

White Rock was allowed to enlist with 11 players, not the required 12, and features a pitcher who opted for Little League after competing in B.C. minor baseball. His nick name is "Tug Boat" and his pitches could spike the price of admission, which is currently nothing.

As of Friday afternoon, White Rock sits atop the round-robin standings with five wins and no losses. New Westminster follows with a 4-2 record and Vancouver's two teams, South Vancouver and Little Mountain, are tied at 3-2. The complete schedule is here.

The top four teams advance to the semi-finals at 3 and 6 p.m. Saturday, July 25. The championship is 2 p.m. Sunday, July 26. The winner earns a sport at the national championship in Ottawa and the chance to represent Canada at the Little League World Series next month.

Before each evening game, which starts daily at 6 p.m., South Vancouver continues to reel in musical talent to sing the Canadian anthem. On Friday, Sarah Johns of Dr. Strangelove will perform. Saturday, it’s jazz vocalist Steve Maddock.

On Sunday, before the Challenger baseball game at 10 a.m., a grandfather of one of the South Vancouver players will light up the mic. That’s Bill Henderson, the singer and songwriter of Chilliwack.

He and his daughters will sing the anthem before the championship game Sunday. Attendance is free.

Read on VanCourier.comVancouver golfer died at Musqueam course doing what he loved.

by Megan Stewart

Posted on July 10, 2015 at 3:27 PM

A threesome reached the 14th green at Musqueam Golf and Learning Academy as Nicholas Trott set up for his tee shot on 15.

Earlier that morning, Trott arrived at the course around 6:30 a.m., as he usually did with his standard poodle Ella, to meet his friends and play a round of golf. For two years, the retired businessman had volunteered as a course marshal, ensuring players kept the right pace, helping others track lost balls, explaining rules to novices, and on Tuesdays, greeting the dozens of women who played that day each week.

His salary was paid in golf, unlimited rounds of golf, often in the morning with friends Marty, Bill and Tom.

“He made friends easily and quickly,” said his wife Gail Meek. “One of his best talents was bringing people together.”

On Friday, July 3, Trott was golfing alone. One friend was at nearby course, two others were taking care of their own responsibilities before they would eventually join him for a few holes. Trott joked with several members of the club’s popular ladies’ league. He talked with a grounds-keeper named Rich and waved at another marshal.

“You always knew when Nicholas was on the course,” said a friend. “He had a big presence. You could hear him from almost everywhere.”

On the 15th hole, not far from the Fraser River, he plunked his Bridgestone on a tee behind the blue markers and selected an iron for the 150-yard par three. Trott shot the ball, and the three women who were still putting on 14 watched as he died on his feet and fell backwards on the grass.

Marty Coulson, a staff member who was part of Trott’s regular foursome, reached the 15th tee box and flagged down another marshal as he called 911. Marty and Bill tried to revive their friend but without success. Trott had a heart attack.

At 71, he was still making connections and friends, offering his shoulder to cry on and making many laugh. As someone pointed out, “71 is one under par.”

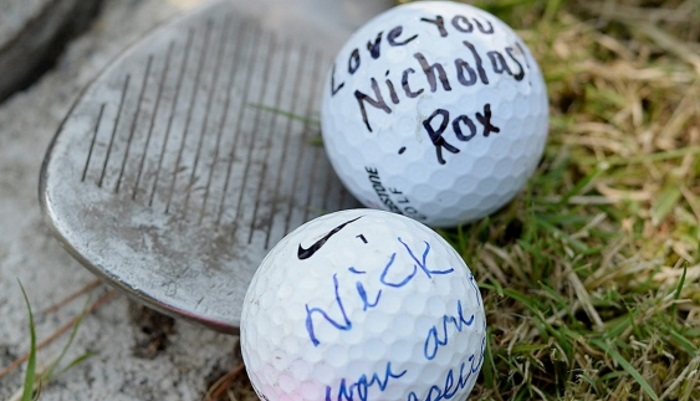

On Tuesday, one golf ball appeared near the tee box at 15. It was a white Bridgestone since Trott was the only one at the club known to use that particular brand. Then, another ball, this one signed. Then a pot of planted purple petunias, a sand wedge and still more balls, many of them with messages.

“The last ball you gave me,” signed in pink felt pen on a Taylor Made.

“We’ll miss you so much, Nichloas.” A heart. RIP.

“Nick, you are so special,” on a Nike ball.

“Helloooo Nick!”

“This is beyond golf,” said the club’s general manager Kumi Kimura. “It’s beyond the game and if it were not for this game, none of us would know each other.”

As another marshal said, “It’s not easy for the people around you when you die instantly. But him, what a better way to go.”

Trott’s friends and the staff at Musqueam looked for the Bridgestone he shot before he died. It’s still lying where it landed, somewhere on the course he loved.

Read on VanCourier.comWomen languish in a league by themselves

by Megan Stewart

Posted on July 7, 2015 at 2:35 PM

My friend was recently watching sports highlights with her daughter when the toddler looked at her mom and asked, “Where are all the girls?”

At three years old, this little sports fan could see what was missing. She was smart enough to ask. She’s smart enough to grasp the discrimination and internalize the absence of people on T.V. who look like her and her mom.

This is why — as much as players, coaches and most of the people involved with women’s sport wish it were otherwise — the Women’s World Cup is still political. The tournament has earned its clout in spite of the double standards every match.

U.S. midfielder Carli Lloyd scored one of the most cunning and audacious goals in the sport’s history by knocking in a shot from the half-way line to notch a hat trick against Japan and win the World Cup this weekend at B.C. Place. But even in praising her, the president of the U.S. Soccer Federation bungled his compliment. “Carli’s performance,” he said, “was as good as any performance in a World Cup Final by any man or female.”

A man is a man, but a woman is a female. Used like this, the word is dehumanizing, but let’s appreciate the applause because in Brazil no one is honouring that country’s superstars. Instead, Marta is still — heartbreakingly — mocked by some, ignored by most and has to put up with ludicrous excuses from her own nation’s representatives who tsk tsk’ed players they claimed lacked “a spirit of elegance, femininity” but cheer those who wear tighter shorts and do their hair. See, my heart breaks. There was no coverage in Brazil after she scored her record 15th World Cup goal, but there was a front-page spread on a friendly between the seleçao and Honduras. More heartbreak.

Despite the record growth of the tournament — 52 soccer matches played by 24 teams over 30 days — it still has the distinction of happening on artificial turf. The plastic was sometimes so hot, players were dousing their feet in water and opting for boots that were any colour but black. More than 40 of them sued FIFA and the host Canadian Soccer Association, but neither would budge.

This disgrace will be borne indefinitely by executives Peter Montopoli and Victor Montagliani, who also have the distinction during this tournament of snubbing the pioneers who once played for Canada when they had no uniforms of their own but dressed in borrowed boys jerseys. Veterans Andrea Neil, Tracy David and others should have been prominent and celebrated by the hosts. Instead, very few Canadians know their names and this is a terrible shame. Christine Sinclair, an icon for millions, had those women as her role models.

Add to this the fact that the U.S. team received $2 million for winning the Cup. Contrast that to the $35 million the German team received for winning the men’s event last year.

This disparity is changing. In the meantime, the leaders of the Canadian Soccer Association are hinting the National Women’s Soccer League may expand in this country from two teams in Quebec to … more? Join me in crossing your fingers.

This is exactly what is needed to capitalize on the attention, interest and investment that has poured into Canada for the World Cup.

The amount of broadcast coverage dedicated to women’s sports, in the U.S. at least, has not increased in 25 years and it still hovers around two per cent, a drop from five per cent in 1989, according to a long-term study by the University of Southern California. A quarter-century of stagnation was blown aside to make way for the FIFA Women’s World Cup, at least temporarily. The question has always been rather chicken and egg: would investment in professional women’s leagues increase if the media paid more attention? Or will the media pay attention once there are leagues to cover? Audiences are saying they will watch.

In 1999, when the U.S. hosted and won the World Cup, 1.1 million people attended matches at stadiums much bigger than ours. This summer, ticket sales jumped to 1.35 million, and more than half of all Canadian girls aged two to 17 watched the World Cup, an increase from one in three in 2011. Women’s World Cup audience records were set for both national languages in this country as well as in the U.S., France, Japan, Australia, China, Korea, Norway and, yes, even in Brazil.

And in my friend’s home, a three-year-old girl watched people like her playing sports on television.

Read on VanCourier.comWorld Cup: Lloyd scores hat trick to push U.S. over Japan

by Megan Stewart

Posted on July 5, 2015 at 6:01 PM

The U.S. idolizes its sports icons, and the country minted a new one Sunday afternoon in Vancouver.

As the smoke from dozens of wild fires dimmed the air inside B.C. Place, U.S. captain Carli Lloyd lit a spark of her own by scoring the fastest hat trick in women’s World Cup history.

The U.S. led 4-0 by the 16th minute.

“Pinch me,” U.S. head coach Jill Ellis said after the match.

“It’s the most ridiculous game I’ve ever been a part of,” said Meghan Klingenberg, a U.S. defender.

“I feel like I blacked out in the first 30 minutes of the game,” said Lloyd, who added she “was on a mission today.”

The New Jersey midfielder scored the winning goal in both the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games, in the latter defeating Japan in penalties. The clutch scorer, who ask her family and fiancé to stay away during the tournament, has learned to go for broke in big matches and visualizes success. In fact, she didn’t see herself scoring three goals to win the World Cup — but more.

“I was home, it was just my headphones, myself and I at the field,” she said in a post-game press conference. “I’m running and I’m doing sprints, it’s hard, I’m burning. I visualized playing in the World Cup Final and visualized scoring four goals. Sounds pretty funny, but that’s what it’s all about”

In front of 53,341 spectators on July 5, the U.S. talent crashed into Japan in the second minute final and didn’t relent until they had clinched their third World Cup with a 5-2 victory.

On the first corner kick, Megan Rapinoe’s cross from the right was flat and fast, beautifully placed to meet Lloyd who streaked in, uncovered, from outside the 18-yard box. She toed the ball into the back of the net with a one-touch shot to give the U.S. a lead it wouldn’t relinquish.

It was one of the best goals of the tournament, if only because the set play was flawlessly executed, catching the Japanese off guard and setting the course for the most important game in four years.

“It seems Lloyd, she always does this to us,” said Japan’s head coach Norio Sasaki, with a gracious smile. “In London she scored two goals and today she scored thee. We are a bit embarrassed, but she is an excellent player so I really respect her and admire her.”

The two teams have traded World Cup and Olympic titles since Japan edged the U.S. in a shoot-out at the 2011 World Cup in Germany. The U.S. had answered three years later when they claimed Olympic gold at the London Games, where they famously plied the referee and broke Canadian hearts.

In this latest meeting, the No. 2 team edged No. 4 to finish first in the world.

In the fifth minute of the final, Lloyd scored her fifth goal in seven games, crashing the net to burry an unclaimed ball. Then, in the 14th minute, Lauren Holiday capitalized on a poorly headed clearance. The ball spinning high above the pitch, Holiday expertly volleyed her shot into the mesh before the ball touched turf.

Then a fourth goal, another from the foot of Lloyd whose horoscope that day said, “Just do what comes naturally.”

In four shots, the U.S. scored four goals.

From the half-way line, Lloyd struck a seeing-eye shot that caught Japan’s keeper Ayumi Kaihori out of position and blinded by the sun shining through the open roof. It was an audacious strike, one that cemented Lloyd the Golden Ball Award as the tournament’s best player and put her only seven minutes’ worth of play time from winning the Golden Boot as the most prolific goal scorer. (That award went to Germany’s Celia Sasic. Both players had six goals and both scored a hat trick, though only one had the distinction of playing in the final. Overall, Sasic played fewer minutes to earn the top prize.)

Japan answered with one of their own when Yuki Ogimi scored her second of the tournament in the 27th minute. Her patient footwork bought enough time in the box for her to slice the ball just out of reach of Hope Solo.

In the second half, Japan counted another goal off a free kick that was placed just in front of Solo. Japan’s Homare Sawa was inches away from putting her head on it, but it didn’t matter because defender Julie Johnston put it in for her, scoring the own goal to bring Japan within two.

One minute later, the U.S. answered with its fifth goal. From the touch line, Morgan Brian passed the ball back into the box to Tobin Heath who scored her first World Cup goal.

Read on VanCourier.comHonour for Britannia's Mike Evans: Never a critic, always a coach

by Megan Stewart

Posted on January 19th, 2016 at 3:57 PM

The hallways at Britannia secondary were buzzing last week before tipoff in the 42nd annual invitational basketball tournament, one of the first in B.C. to host senior boys and girls at the same time, same place.

The excitement was about that place, specifically the Bruins basketball court and its flanking bleachers, and about one person, a coach who since 1980 has made that gym a second home not only for himself but also a welcoming and safe space for hundreds of teenage athletes.

On Jan. 14 before the senior girls won their own tournament for a ninth time in 11 years, the school paid special tribute to Bruins coach Mike Evans. They named the place after him.

More than 120 former student-athletes and numerous retired teachers dressed in red and walked out on the floor. The stands were already packed. As Evans led the Bruins in a pre-game pep talk under blue banners for city and regional championships and their cherished 2012 B.C. AA title, the players made sure to hold his attention and keep his back to the larger crowd. Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” blared on the PA. The reveal was a surprise.

Evans, whose first day as a counsellor at Britannia was in 1980, turned around to see a few words newly printed on the wall: Mike Evans Gymnasium.

“I wonder if it’s legal, but anyway…” Evans said a few days later, characteristically humble and funny. “It was overwhelming and as it turns out, it was a well-kept secret.”

Mitra Tshan, the bantam and junior girls coach as well as a community educator at Britannia, organized the ceremony with Trevor Stokes, who coaches with Evans and teachers in the Streetfront alternative school, and Bob Fitzpatrick, an I.B. teacher and student council sponsor. The name reveal was public knowledge and widely shared on social media, but Evans said he was none the wiser.

“It was a complete surprise and a shock at first. You could probably list quite a few people, some of whom have retired long ago who have put in a lot of time and who are legendary in the history of this school. The gym was built in the ’50s even though the school itself is 100 or so years old. I feel very humbled that there are some pretty famous people who did not have a gym named after them. There are other worthy people, too,” said Evans.

“I’m aware of other schools where gyms have been named after people, who I knew as well. Maybe it’s a little unusual that I’m not a PE teacher. Others tended to be PE teachers who lived in the gym, though I lived there, too.”

Evans, a NCAA Div. 1 middle-distance sprinter, came to Britannia in 1980 as a counsellor and began to build a broad network for students, including the many immigrants and refugees who arrived in Canada in the ’70s and ’80s from Southeast Asia and China. According to biography prepared by Stokes, 30 years ago Evans “set the standard for how a school was to going to best address the specific needs and desires for these vulnerable students. His work with the ESL Project is still commented on and used as an example.”

He coached the senior boys basketball team — as well as many others since he identified sports as an effective and meaningful way to engage students — and in 1987 he was approached by a few young women. “That one nervous request started his legacy,” wrote Stokes.

“I have been teaching here for 42 years and we will never see the likes of Mike Evans again at Britannia secondary,” said Fitzpatrick in an interview Tuesday.

Britannia Bruins senior girls basketball coach Mike Evans huddles with players moments before the gym was named in his honour Jan. 14, 2016. Photos Dan Toulgoet He added that Evans has high expectations for his players. “He treats them as equal. He’s a no-nonsense basketball coach. He does not allow them to play any cards, if you know what I mean. And it’s no surprise that many of these basketball players are also excellent students.”

Fitzpatrick described a coach who works 24 hours a day, seven days a week to help kids succeed.

“This has carried over to the men’s team because success breeds success and it’s also carried over to keeping kids in school. It helps keep marginalized kids in school because they are experiencing success,” he said. “Mike is a coach, not a critic.”

Evans was a counsellor until 2002 and then became a community school education coordinator for the high school and its associated elementary schools. He retired in August and for nearly 40 years has lived in Ladner with his wife, Pat. Their daughter is an elementary school teacher in Vancouver.

Now in his 70s, Evans will continue coaching the Bruins and is taking the year to work out an adjusted schedule. “If there’s a practice at 3:30 p.m., I leave for the school at 2 p.m. If there’s a practice at 5 p.m., I leave at 2 p.m.,” he said. “Because of the traffic.”

He is part of the Britannia Support Society, which raises money to enrich the lives of students. And he is also on the board of CLICK (Contributing to the Lives of Inner City Kids).

“Plus I’m coaching,” he said. “I don’t really see an end in sight.”

Honour Roll

At Vancouver secondary schools, the Mike Evans Gymnasium is on a short list of gyms named for influential coaches. Evans was a counsellor and in the case of these five other schools, the coaches whose names are now on the gymnasiums were also respected teachers.

- Eric Hamber secondary: Norma McDermott and Bruce Ashdown

- John Oliver secondary: Hugh Marshall and Mary Macdonald

- Killarney secondary: Dave Renwick and the main basketball court named after Tom Tagami

- Kitsilano secondary: Stan Lawson and Loma McKenzie

- Prince of Wales secondary: Bill Seggie and Darlene Currie

Hockey Night in Mongolia

by Megan Stewart

Posted on January 18th, 2016 at 1:23 PM

A mere 80 kilometres from the Russian border in northern Mongolia, Nate Leslie got a phone call from a hockey coach in an even smaller, even more remote town than the one he was in. The coach was pleading with Leslie to make the two-hour drive on a road that only exists when the temperature settles well below freezing.

“They’d heard about the Canadians,” said Leslie, a retired professional player who now holds skills camps and trains coaches the world over with the company he runs with his brother, Leslie Global Sports.

“Our host didn’t even know they had a rink,” he added during an interview last week.

The Vancouver hockey coach finished one training session and then set out for the next town, arriving after 7 p.m. “It was pitch black, and the kids skating on the ice had been there since two in the afternoon, hoping we’d show up,” he said. “We used the lights off the cameras and the headlights of two cars and we lit a corner of the ice and did skating drills.”

In a country with just 10 ice rinks that are, incredibly, all outside and managed by hand often with cold water, players have a level of passion that far surpasses their skill, their limited training and the few pairs of skates that are passed around and shared. That’s what drew Nate Leslie and his brother Boe Leslie to Mongolia in the first place. In the country’s expansive, rural tundra, its competitive spirit and passion for winter sport, they recognized many of the same features that characterized their youth. (“I eyeballed the longitude and it’s roughly like central Manitoba, very similar to the Canadian Prairies, land-locked, dry and cold in a similar way,” said Leslie.)

The brothers grew up playing elite hockey in Manitoba. Boe competed in the NCAA and both played professionally in Europe. They transitioned to management, coaching players and also to coaching coaches through their sports leadership company and the website How to Play Hockey. (“Dot ca,” Leslie was proud to spell out.)

One day three years ago, he was notified that a new coach was signing up to the site using an email address that was adorned with a small flag of Mongolia (which Leslie knew because he immediately looked it up).

“Six years ago they didn’t have that [Internet] access, now they can watch NHL games on YouTube,” he said. “We got to talking, and we instantly sponsored all of our coaching products and knowledge by giving it away for free.”

The shortened version of the Mongolian coach’s name is Pujee but his name and title is much more. Purevdavaa "Pujee" Choijiljav is the General Secretary of the Mongolian Hockey Federation and is widely considered, as the Leslie brothers learned, his country's grandfather of hockey. He also became their host when, last February, the brothers travelled to Ulaanbaatar along with a documentary film crew that included cameraman Patrick Bell and editor Rob Postma, both of Vancouver, and CBC sports journalist Karin Larsen, the project’s writer and whose children played hockey for Leslie.

Their documentary, Rinks of Hope: Project Mongolia, screens to a sold-out audience tonight at Vancity Theatre. A second screening is planned for March at UBC.

The Canadians volunteered to help develop youth hockey in Mongolia and along with their expertise, they brought 60 pairs of skates, 60 sticks and other equipment with them. That gear meant about 180 people could play because the equipment was shared. The NHLPA also donated 40 jerseys and late last year shipped 25 pairs of kids skates.

“If I did it again, I would just have taken skates and sticks because that’s all they need to get playing. They didn’t even wear mitts, definitely not hockey gloves,” said Leslie.

The brothers ran practices with 320 players and coaches and visited seven of the country’s 10 ice rinks, all of them outdoors. Thanks to additional donors, they distributed more than 100 sets of hockey gear and intend to return with more.

A typical day, described by Leslie, included, “The mayor of town standing there watching, a nomadic sheepherder watching with this cellphone filming us, and other coaches out on the ice in boots filming drills so they can remember them for later. With the exception of the capital, that’s what you’d expect.”

Larsen said many Mongolians, like Canadians, love playing sports and have a “huge appetite” for hockey. They also ride and race horses, and about a third of the population still pursues a nomadic lifestyle.

“The Mongolian kids were just so joyful when they were on the ice and would stay in -25 C all day if you let them. Nate and Boe had to reconsider their own level of toughness each day because they'd be freezing and wanting off, and the kids just wanted to keep playing,” wrote Larsen in an email.

“The big issue was always equipment. The kids may have skates — usually three sizes too big because adult gear is a little easier to come by — and an old stick that would have long ago been thrown away in North America, but that was about it. Pretty stark comparison to the situation in Canada where you see atom-age players with $500 skates and $300 sticks and shooting coaches and skating coaches...”

With some development and investment, the last-ranked hockey playing nation doesn’t just have a future in the sport but a bright one at that, said Larsen, herself an Olympian synchronized swimmer.

“The passion for hockey in Mongolia is the same as in Canada, they just don't have the resources yet. Could be scary in the future [because] the kids were really good athletes, tough and strong, and picked skills up really quickly,” she wrote.

Leslie said the players — who were of all ages from six to beyond 66 — went hard but with a few exceptions, their skills didn’t yet match their enthusiasm.

“The skill level was very rusty, sort of like an average house league here. But they go so hard, borderline recklessly,” he said. “We joked that if they ever get his hockey thing figured out, we in Canada are in trouble because they’re so tough and so resilient and hard-working.”

To learn more or donate to the project, visit the documentary's page on Kickstarter.

Read on VanCourier.comRower prepares for ‘biggest, baddest’ endurance race across Pacific

by Megan Stewart

Posted on January 27th, 2016 at 1:39 PM

Perched on the tiny seat of a stationary rowing machine on the ground floor of the International Boat Show at B.C. Place, Brenda Robbins was a quarter of the way to her destination when “mind over matter” simply wasn’t enough to power her anymore.

Starting at 10 a.m. Jan. 20, she started gunning for a Guinness World Record. To meet it, she’d have to stay on that seat, rowing until Saturday night. Rowing for the next 81 hours.

“I learned that the psychological challenge is even more challenged than I ever imagined,” she said after she stopped her row the next day at noon. “Upon reaching that physical limit when pain is setting in and sleep deprivation is having its effects, the will to keep going was the biggest limit I hit.”

Robbins, who grew up in land-locked town in Manitoba and now calls the West End home, said the feeling was surreal. She couldn’t will her body forward. She rowed for 26 hours, setting a women’s record in the effort to row nearly three times longer.

“When the physical challenge hit its limit — pain, exhaustion, dizziness — I was surprised that I wasn't better able to overcome it psychologically, to tell my mind to push through it,” she said.

Daring to be great

In the tremendous effort, Robbins moved at a slow pace but nonetheless rowed nearly 175 kilometres at seven km/h.

But in fact, her record row is just the warm-up for a much more significant feat. This summer, Robbins will attempt to cover nearly 4,000 km — 2,400 miles as a straight line but more like 3,000 miles because of wind, waves and open water — from California to Hawaii as part of a four-woman team in the Great Pacific Race. If successful, they will be the second women’s foursome to complete the feat and Robbins will be the first Canadian to row across the Pacific Ocean.

Naturally, she and the Daring Greatly Crew want to break a record and set the benchmark as the fastest women’s team to make the journey. They will aspire to cover between 50 and 70 miles each day. Robbins has yet to meet her teammates in person.

“When I first got interested in ocean rowing, the record didn’t appeal to me at all,” she said. “I just wanted to get on the ocean and pursue my own journey across. But you learn about the records and other people who are making attempts, and it’s like, I can do that. They are goals within a goal. There is something to that.”

Oceanwise

In their own words, the Great Pacific Races is “the biggest, baddest human endurance challenge on the planet.” Open row boats with international crews of two or four people compete in this epic journey. The modern, Western history of open ocean rowing dates to 1896 when a 10,000 cash prize spurred two New Jersey fisherman to test themselves on the Atlantic. The first successful crossing of the Pacific was recorded in 1971.

Robbins is preparing to spend between 30 and 80 days at sea without sails or engines, rowing for two hours and resting for the next two before picking up the oars for two more hours and then repeating until her team reaches Waikiki Beach.

“You can always adjust it as the team feels is needed though the longer a break you take, the longer you will be rowing as well. This is conventional and seems to be the tried-and-true method of all the ocean teams.

“I’m very motivated,” she said. “Right away, it was in my head that I wanted to do this.”

She learned about the Great Pacific Race following its inaugural year in 2014 and immediately set out to learn everything she could.

Robbins launches out of Jericho Sailing Club, mostly to paddle and kayak, and keeps a stationary rowing machine in her apartment. She planned a solo row of the Atlantic, but left that to pursue the Great Pacific Race.

She will try to consume roughly 5,000 calories a day through high-caloric freeze dried food. During her 26-hour indoor row, she ate salmon, fruit, coconut oil on crackers, and protein smoothies. She was able to take a 10-minute break every hour.

On the ocean, there will be little reprieve, but getting there is one of the biggest challenges.

“They say that, even hard than rowing the ocean, is getting prepared for the race financially and logistically,” said Robbins.

Rowing for blood

She is fundraising through GoFundMe for her transportation to California and for supplies during the trip. Her goal is $45,000 and she is also raising money to donate to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of Canada.

Robbins’ father died in 2015 of acute leukemia.

“He was really easy to get along with even when it came to having a terminal illness, he never complained and he was a really positive and supportive person,” she said.

“I feel that he always had confidence in me. Whatever I set my mind to, I would follow through on and do it safely and to the best of my ability.”

Follow Robbins’ preparation and race on her blog at rowforblood.ca.

Read on VanCourier.comBlog Categories

- Bird brainiacs: Where tech meets bird-watching

- Love on the run: Couple to wed during Vancouver marathon

- Vancouver grandmother on risks and metaphysics before Marathon Des Sables

- Needle sweeps part of morning routine at Strathcona playground

- Little League: Loverboy sings the anthem, ‘Iron Pony’ next at bat

- Vancouver golfer died at Musqueam course doing what he loved.

- Women languish in a league by themselves

- World Cup: Lloyd scores hat trick to push U.S. over Japan

- Never a critic, always a coach

- Hockey Night in Mongolia

- 'Biggest, baddest' endurance race